Original article: Colera – descrizione della patologia ed approfondimenti, by Ilaria Salvatori

Characteristics of the disease

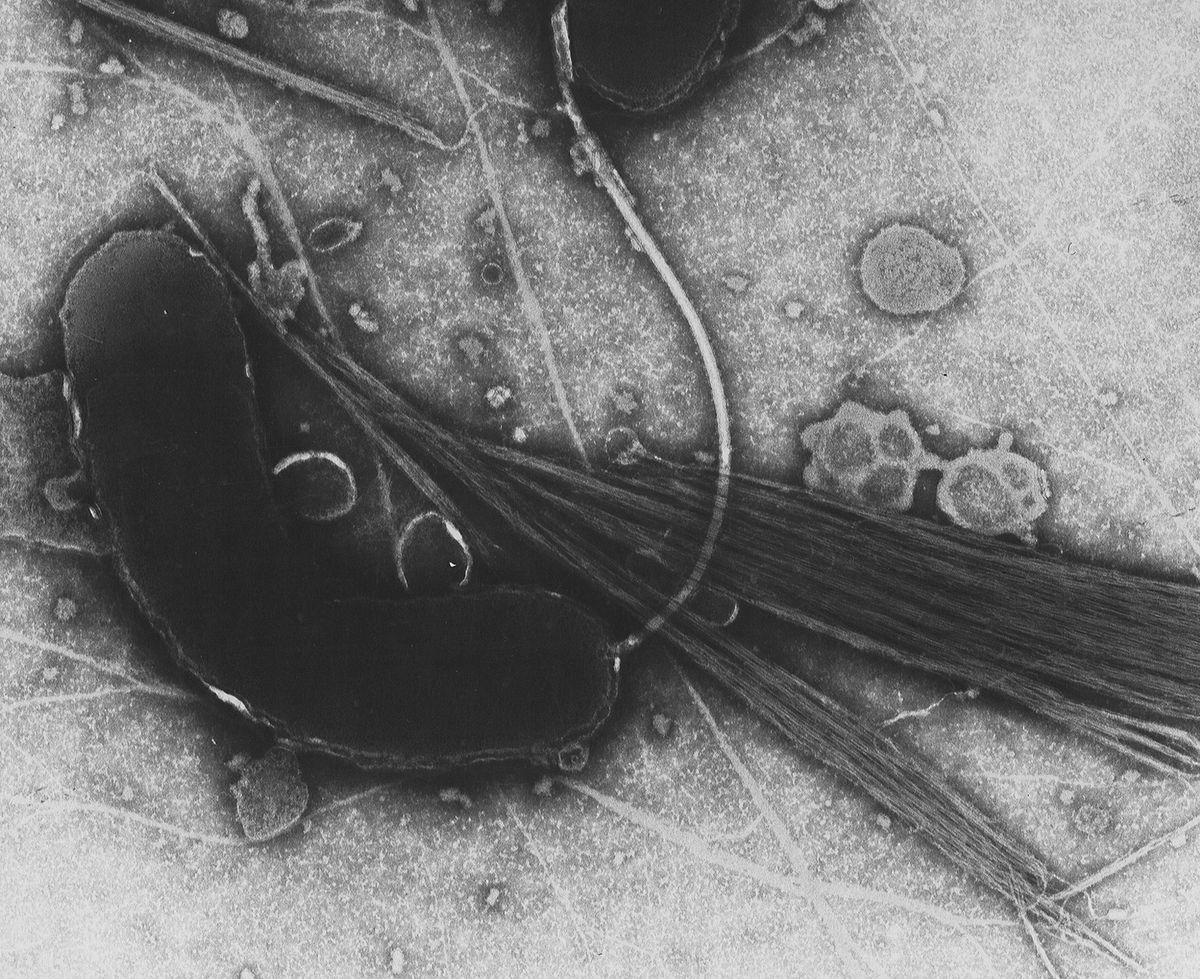

Cholera is an acute diarrheal infection caused by the ingestion of contaminated food or water by a particular Gram (-) bacterium with a characteristic comma shape: Vibrio cholerae.

The main sign of the disease is the presence of watery diarrhea, also called “rice-water,” characterized by massive fluid loss (up to one liter per hour) and the almost complete or total absence of stool. Most patients do not experience pain or tenesmus, but vomiting and cramping may appear in some cases.

The loss of fluids leads to a series of essential complications that, if not contained quickly, can lead to the death of the patient. One of the major problems is the electrolyte imbalance due to dehydration: the loss of water is associated with the elimination of electrolytes such as sodium, potassium, and calcium, which are essential for maintaining homeostasis.

Signs and Symptoms

The first symptoms begin to appear after an incubation period of about 3 days, and the onset is generally abrupt but characterized by the absence of fever. The most prominent clinical signs are:

- Abrupt diarrhea: sudden, harsh, with persistent discharges;

- Stools: present only in small quantities (50 to 100 ml), with the possible presence of mucus;

- Vomiting: present only in some cases;

- Signs of acute dehydration: dryness of mucous membranes, thirst, dry tongue, and lips;

- Electrolyte alterations: decreased calcium, potassium, and bicarbonates;

- Algidism: cold skin;

- Decreased blood pressure.

Potassium is a mineral indispensable for the optimal functioning of the body and is the principal intracellular cation. Its presence in the body is essential because it allows muscle contraction, the transmission of nerve impulses, regulates many cellular processes, and is involved in maintaining homeostasis. On the other hand, sodium is the most critical extracellular cation involved in various vital functions such as pressure regulation, promotes neuromuscular function and nerve impulse transmission, and regulates fluids and nutrients inside/outside the cell.

Secondary effects

Secondary effects to watery diarrhea include:

- Lethargy

- Alterations in consciousness

- Muscle cramps

- Hypotension

- Renal failure

- Hypovolemic shock

Another side effect is acidosis: hyponatremia (sodium deficiency) and bicarbonate loss lead to a condition of acidosis associated with increased blood concentration.

However, signs and symptoms are not present in all those who contract the disease: in 75% of cases, infected people do not show any symptoms. However, only a tiny part develops the severe form of the disease among those who do show them. Thus, cholera can present itself either as an acute (and potentially lethal) event or in a mild form.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The etiologic agent of cholera is Vibrio cholerae, a bacterium belonging to the Vibrionaceae family.

Within the genus Vibrio, there are 3 hazardous bacteria for humans as human pathogens: Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio vulnificus and Vibrio parahemolyticus. Vibrio cholerae is undoubtedly the most dangerous because, besides being more virulent, it is the only one capable of growing both in marine and freshwater environments.

There are many serogroups of V. cholerae, approximately 200, but only a few are capable of causing the disease. The serogroups can be essentially divided into two types, depending on their ability to produce cholerae toxin:

- Cholera toxin-producing groups: this group contains the serotypes most implicated in the development of the disease, serotype O1, and serotype O139. Serotype O1, in particular, is divided into the “Classic” and “El Tor” biotypes, also referred to as epidemic strains;

- Groups that do not produce the cholera toxin: this group contains serotypes generally associated with only a few sporadic cases.

The pathogenicity of V. cholerae is associated with its ability to produce cholera toxin. Once introduced inside the organism, cholera vibrios reach the intestinal lumen adhering to it through flagellar proteins. Once arrived in the host’s intestine, the bacterium releases a thermolabile toxin, responsible for the increase of AMPcyclic in the cell, with consequent reduction of sodium absorption and increase of chlorine secretion. This electrolyte imbalance leads to fluid accumulation in the intestinal lumen, resulting in watery diarrhea.

Transmission

The primary source of contamination is the presence of bacteria in the feces of an infected person. In addition, an individual can be infected indirectly by drinking water or eating food contaminated with bacteria. Common sources of foodborne infection include raw or poorly cooked seafood, raw fruits and vegetables, and other foods contaminated during preparation or storage. The foodstuffs most at risk are mollusks which, being burrowing and filtering animals, are more likely to accumulate bacteria and viruses present in the environment.

The infectious dose is about 108 u.f.c. but, in the presence of some predisposing factors, it is lowered to about 103-105 u.f.c. One of the factors predisposing to infection is reduced gastric acidity, as the acid content of the stomach can determine a partial degradation of the bacteria.

Epidemiology

Cholera has very ancient origins: some Sanskrit writings of the fifth century described a disease similar to cholera. Since ancient times cholera afflicts many populations and is currently endemic in over 50 countries. The first essential studies were carried out between 1849 and 1884. In 1854, Filippo Pacini observed in the feces of infected patients some comma-shaped bacteria, later isolated in 1883 by Robert Koch.

Historians and epidemiologists agree that seven cholera pandemics have occurred since 1817, caused mainly by the Classical biotype. The seventh pandemic began in Indonesia in 1961 and spread through Asia to Africa, Europe, and Latin America. The latter, in particular, differed from previous ones in that the El tor biotype caused it.

Cholera appeared for the first time in Europe and, therefore, in Italy in the first half of the 19th century: the fourth pandemic, which lasted from 1863 to 1875, mainly affected southern regions such as Apulia and Campania. The seventh epidemic also disturbed the balance of the Italian population: in 1973, cholera landed in Campania. One of the first areas affected was the Vesuvian village of Torre del Greco, known for its flourishing fish trade. This sudden epidemic, which reached the city of Naples in a short time and caused in this region only 15 deaths, is remembered for the timely preventive measures that were put in place. In 7 days, about 1 million people were vaccinated, thanks to the use of syringe guns used in Vietnam by the Americans.

Current situation

Cholera remains a global public health threat and an indicator of social inequality, as it predominantly affects areas of low socioeconomic development. A predisposing factor for developing the disease can be found in the poor hygienic conditions that characterize many developing countries. In addition, the absence of sewers, sanitation facilities, and water sanitation systems leads to more significant and more likely contamination.

In endemic countries, there are an estimated 2.86 million cases of cholera each year. The countries most at risk are India, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Haiti, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Tanzania, Kenya, and Bangladesh. In addition, although classified as non-endemic, Pakistan, Bolivia, and Sri Lanka have an average of about 2,737 reported cases each year. In recent years, devastating cholera outbreaks have occurred in Angola, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, Pakistan, Somalia, Sudan, Vietnam, and Haiti.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of cholera is primarily based on the analysis of stool samples. Once the sample has been collected, the bacterium is isolated using specific culture media such as TCBS (Thiosulfate citrate bile salts sucrose agar), representing the ideal selective and differential medium for the isolation and culture of V. cholerae from clinical specimens. Another widely used medium is TTGA (Taurocholate tellurite gelatin agar), specifically formulated for the selective and differential isolation of V. cholerae.

In some cases, especially in the absence of suitable laboratories and/or equipment, rapid tests can be used. Although these tests have low specificity and sensitivity and can in no way replace traditional isolation methods, they are a valuable aid in monitoring the spread of the disease in high-risk areas. One of the most widely used rapid tests is the Crystal VC (RTD), a dipstick test based on the detection of lipopolysaccharide O of V. cholerae by monoclonal antibodies and uses vertical flow immunochromatography and antibodies conjugated to colloidal gold particles for antigen detection.

Instrumental and laboratory tests

Culture media represent the ideal method for the isolation and identification of V. cholerae. However, in some cases, especially when the TCBS medium is not selective enough and allows the growth of competitors such as Aeromonas and Pseudomonas, biochemical tests can be used. Among these, we have:

- Oxidase test

- String test

- Carbohydrate fermentation test

- Voges-Proskauer test

Therapy

Therapy is mainly based on patient rehydration through sodium chloride solutions, sodium bicarbonate, potassium chloride, and dextrose. Potassium levels must be kept under control: to replace the loss of potassium, 10 to 15 mEq/L (10 to 15 mmol/L) of potassium chloride can be added to the solution. The WHO recommends using an oral solution containing 13.5 g glucose, 2.6 g NaCl, 2.9 g trisodium citrate dihydrate, and 1.5 g KCl per liter of drinking water.

Initially, when the patient is in critical condition, he or she should be immediately rehydrated. In patients in shock, the amount of fluids should reach approximately 10% of body weight, while 2.5% of body weight is reached in less severe cases. Once the volaemia is re-established, the treatment is based on the amount of liquids lost with urine, feces, and vomit, to which 500 ml are added.

The use of antibiotic therapy is also possible, mainly aimed at shortening the course of the disease and reducing the intensity of symptoms. The most commonly used antibiotics are erythromycin, tetracyclines, and doxycycline.

Prevention

A preventive approach is of relevant importance to limit the number of cholera cases and reduce mortality. One of the first preventive interventions certainly requires the sanitization of areas at risk (water purification, elimination of excrements) and the improvement of sanitary facilities. It is also essential to ensure food safety: in endemic regions, it is preferable to boil or chlorinate drinking water, while vegetables and fish must be consumed after proper cooking.

There are currently 4 types of vaccines available against cholera. The Vaxchora vaccine is the safest and most effective, as it can reduce the possibility of severe diarrhea by 90% at 10 days after vaccination and by 80% at 3 months after vaccination. However, there is still a lack of information regarding the safety and efficacy of this vaccine in pregnant or lactating women. In general, however, it is important to point out that cholera vaccines offer incomplete protection, so it is important to follow good hygiene and preventive measures.

Ilaria Salvatori

Bibliography

- https://www.who.int/topics/cholera/faq/en/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3761070/#R5

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4455997/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673674922338

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12738652/

- https://www.msdmanuals.com/it-it/professionale/malattie-infettive/bacilli-gram-negativi/colera

- https://www.epicentro.iss.it/colera/

- https://www.cdc.gov/cholera/laboratory.html

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epidemia_di_colera_in_Italia_del_1973

- https://www.vesuviolive.it